THE 4000-YEAR HISTORY OF VIETNAM

Vietnam, with its coastal strip, rugged mountainous interior, and two major deltas, became home to numerous cultures throughout history. Its strategic geographical position in Southeast Asia also made it a crossroads of trade and a focal point of conflict, contributing to its complex and eventful past. The first Acient East Eurasian hunter-gathers arrived at least 40,000 years ago. Around 4,000 years ago during the Neolithic period, Ancient Southern East Asian populations, particularly Austroasiatic and Austronesian peoples, began migrating from southern China into Southeast Asia, bringing with them rice-cultivation knowledge, languages and much of the genetic basis of the modern population of Vietnam. In the first millennium BCE the Đông Sơn culture emerged, based on rice cultivation and focused on the indigenous chiefdoms of Văn Lang and Âu Lạc.

Following the 111 BCE Han conquest of Nanyue, much of Vietnam came under Chinese dominance for a thousand years. The period nonetheless saw numerous uprisings, and Vietnamese kingdoms occasionally enjoyed de facto independence. Buddhism and Hinduism arrived by the 2nd century CE, making Vietnam the first place which shared influences of both Chinese and Indian cultures.

Independence was regained when the Ngô dynasty was established in 939, and the next millennium saw a succession of local dynasties: Ngô, Đinh, Anterior Lê dynasty, Lý, Trần, Hồ, Lê, Mạc, Revival Lê, Tây Sơn, and finally Nguyễn. During this period, Vietnam was periodically divided by civil wars, most notably the Trịnh–Nguyễn War of the 17th and 18th centuries, and subjected to foreign interventions by the Song, Yuan, Cham, Ming, Siamese, Quing, and finally the French. In their turn Vietnamese colonizers moved into the Mekong Delta and parts of today's Cambodia between the 15th and 18th centuries.

Leveraging its military support for the ascendant Nguyễn dynasty and using the pretexts of protecting religious freedom and trading rights, France conquered Vietnam, dividing its territory into three separate regions, integrating them into French Indochina in 1887. The World War II brought a 5-year occupation by Imperial Japan. In 1945 Vietnam was proclaimed a republic, but a three-way conflict immediately broke out between communists, anti-communists, and France. In 1949 Vietnam was officially reunified as a partially autonomous member of the French Union. In practice, a communist insurgency led by Ho Chi Minh had established a rival state which exercised authority over most of the country. Following the French defeat, the country was divided into two states in July. As part of the Cold War, a war quickly broke out between a North Vietnam supported by China and the Soviet Union, and a South Vietnam aided by the United States. It ended with the defeat of the South in 1975 and unification under a communist government in 1976. Vietnam then fought a war with China in 1979 and was bogged down in Cambodia from 1978 to 1989, along with an economic disaster that led to Đổi Mới in late 1986. Vietnam normalized relations with China in 1991 and the United States in 1995.

Let's Start A Journey Through Time

Đông Sơn culture and the Legend of Hồng Bàng dynasty

According to a Vietnamese legend which first appeared in the 14th century book Lĩnh Nam chích quái, the tribal chief Lộc Tục (c. 2919 – 2794 BC) proclaimed himself as Kinh Dương Vương and founded the state of Xích Quỷ in 2879 BC, that marks the beginning of the Hồng Bàng dynastic period . However, modern Vietnamese historians assume, that statehood was only developed in the Red River Delta by the second half of 1st millennium BC. Kinh Dương Vương was succeeded by Sùng Lãm (c. 2825 BC – 2525 BC). The next royal dynasty produced 18 monarchs, known as the Hùng kings, who renamed their country Văn Lang. The administrative system includes offices like military chief (lạc tướng), paladin (lạc hầu) and mandarin (bố chính). Great numbers of metal weapons and tools excavated at various Phung Nguyen culture sites in northern Indochina are associated with the beginning of the Copper Age in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, the beginning of the Broze Age has been verified for around 500 BC at Đông Sơn. Vietnamese historians usually attribute the Đông Sơn culture with the kingdoms of Văn Lang, Âu Lạc, and the Hồng Bàng dynasty. The local Lạc Việt community had developed a highly sophisticated industry of quality bronze production, processing and the manufacturing of tools, weapons and exquisite Bronze drums. Certainly of symbolic value, they were intended to be used for religious or ceremonial purposes. The craftsmen of these objects required refined skills in melting techniques, in the lost-wax casting technique and acquired master skills of composition and execution for the elaborate engravings

Âu Lạc kingdom (257 BC – 179 BC)

By the 3rd century BC, another Viet group, the Âu Việt, emigrated from modern-day southern China to the Hồng River delta and mixed with the indigenous Văn Lang population. In 257 BC, a new kingdom, Âu Lạc, emerged as the union of the Âu Việt and the Lạc Việt, with Thục Phán proclaiming himself "An Dương Vương" ("King An Dương"). Some modern Vietnamese believe that Thục Phán came upon the Âu Việt territory (modern-day northernmost Vietnam, western Guangdong, and southern Guangxi province, with its capital in what is today Cao Bằng province).

Nanyue (179 BC – 111 BC)

IIn 207 BC, the former Qin general Zhao Tuo (Triệu Đà in Vietnamese) founded an independent kingdom in the present-day Guangdong/Guangxi region on China's south coast. He declared it as Nam Việt (pinyin: Nanyue), to be ruled by the Zhao dynasty. Zhao Tuo later appointed himself a commandant of central Guangdong, closing the borders and conquering neighboring districts and titled himself "King of Nanyue". In 179 BC, he defeated King An Dương Vương and annexed Âu Lạc.

The period has been given some controversial conclusions by Vietnamese historians, as some consider Zhao's rule as the starting point of the Chinese domination, since Zhao Tuo was a former Qin general; whereas others consider it still an era of Vietnamese independence as the Zhao family in Nanyue were assimilated into local culture. They ruled independently of what then constituted the Han Empire. At one point, Zhao Tuo even declared himself Emperor, equal to the Han Emperor in the north.

First Era of Northern Domination (111 BC – 40 AD)

In 111 BC, the Chinese Han dynasty conquered Nanyue and established its new territories, dividing Vietnam into Giao Chỉ (pinyin: Jiaozhi), i.e. the Red River Delta; Cửu Chân from Thanh Hóa to Hà Tĩnh; and Nhật Nam (pinyin: Rinan), from Quảng Bình to Huế. While governors and top officials were Chinese, the original Vietnamese nobles (Lạc Hầu, Lạc Tướng) from the Hồng Bàng period still managed in some of the highlands. During this period, Buddhism was introduced into Vietnam from India via the Maritime Silk Road, while Taoism and Confucianism spread to Vietnam through the Chinese rulers.

Trưng Sisters' rebellion (40 AD – 43 AD)

February AD 40, the Trưng Sisters led a successful revolt against Han Governor Su Ding (Vietnamese:Tô Định) and recaptured 65 states (including modern Guangxi). Trưng Trắc, angered by the killing of her husband by Su Dung, led the revolt together with her sister, Trưng Nhị. Trưng Trắc later became the Queen (Trưng Nữ Vương). In 43 AD,Emperor Guangwu of Han sent his famous general Ma Yuan (Vietnamese: Mã Viện) with a large army to quell the revolt. After a long, difficult campaign, Ma Yuan suppressed the uprising and the Trung Sisters committed suicide to avoid capture. To this day, the Trưng Sisters are revered in Vietnam as the national symbol of Vietnamese women.

Second Era of Northern Domination (43 AD – 544 AD)

Learning a lesson from the Trưng revolt, the Han and other successful Chinese dynasties took measures to eliminate the power of the Vietnamese nobles. The Vietnamese elites were educated in Chinese culture and politics. During the end of the Han and beginning of the three kingdoms era, the Giao Chi prefect Shi Xiep professed allegiance to the emperor and then Wu—including sending a son as a hostage to ensure his loyalty—but is regarded by Vietnamese historiography has having been an autonomous warlord, posthumously deified by later Vietnamese monarchs. According to Stephen O'Harrow, Shi Xie was essentially "the first Vietnamese". Upon Shi's death, Wu ordered the separation of Guangzhou as a new province and the replacement of Shi's son as head of Giao Chi. Shi Hui rebelled but aimed for a peaceful resolution once the Wu army arrived. During negotiations, he and most of his brothers were executed and the remainder of his family demoted to common status. In 248, a Yue (Viet in Vietnamese) woman,Triệu Thị Trinh (popularly known as Lady Triệu), led a revolt with her brother Triệu Quốc Đạt against the Wu Kingdom. Once again, the uprising failed. Eastern Wu sent Lu Yin and 8,000 elite soldiers to suppress the rebels.He managed to pacify the rebels with a combination of threats and persuasion. According to the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Complete Annals of Đại Việt), Lady Triệu had long hair that reached her shoulders and rode into battle on an elephant. After several months of warfare she was defeated and committed suicide. A more successful revolt occurred in the mid-260s when the county official Lü Xing (呂興) overthrew the rest of the Wu administration and reached out to Wei's governor of recently conquered Shu. Wei and its successor state Jin held Giao Chi from 266 to 271, when Wu's Jiaozhi Campaign finally reconquered the area. It returned to Jin's control, however, following its complete annexation of Wu, ending the Three Kingdoms period.

Kingdom of Vạn Xuân (544 AD – 602 AD)

In the period between the beginning of the Chinese Age of Fragmentation and the end of the Tang dynasty, several revolts against Chinese rule took place, such as those of Lý Bí (Lý Nam Đế) and his general and heir Triệu Quang Phục (Triệu Việt Vương). All of them ultimately failed, yet most notable were those led by Lý Bôn and Triệu Quang Phục, who ruled the briefly independent Van Xuan kingdom for almost half a century, from 544 to 602, before Sui China reconquered the kingdom.

Third Era of Northern Domination (602 AD – 905 AD)

During the Tang dynasty, Vietnam was called Annam until AD 866. With its capital around Bắc Ninh, Annam became a flourishing trading outpost, receiving goods from the southern seas. The Book of the Later Han recorded that in 166 the first envoy from the RomanE Empire to China arrived by this route, and merchants were soon to follow. The 3rd-century Tales of Wei mentioned a "water route" (the Red River) from Annam into what is now southern Yunnan. From there, goods were taken over land to the rest of China via the regions of modern Kunming and Chengdu. The capital of Annam, Tống Bình or Songping (today Hanoi) was a major urbanized settlement in the southwest region of Tang Empire. From 858 to 864, disturbances in Annan gave Nanzhao, a Yunnan kingdom, opportunity to intervene the region, provoking local tribes to revolt against the Chinese. The Yunnanese and their local allies launched the Siege of Songping in early 863, defeating the Chinese, and captured the capital in three years. In 866, Chinese jiedushi Gao Pian recaptured the city and drove out the Nanzhao army. He renamed the city to Daluocheng (大羅城, Đại La thành).

In 866, Annam was renamed Tĩnh Hải Quân. Early in the 10th century, as China became politically fragmented, successive lords from the Khúc clan, followed by Dương Đình Nghệ, ruled Tĩnh Hải quân autonomously under the Tang title of Jiedushi (Vietnamese: Tiết Độ Sứ), (governor), but stopped short of proclaiming themselves kings.

Autonomous Era (905 – 938)

Since 905, Tĩnh Hải circuit had been ruled by local Vietnamese governors like an autonomous state. Tĩnh Hải circuit had to paid tributes for Later Liang Dynasty to exchange political protection. In 923, the nearby Southern Han invaded Jinghai but was repelled by Vietnamese leader Dương Đình Nghệ. In 938, the Chinese state Southern Han once again sent a fleet to subdue the Vietnamese. General Ngô Quyền (939–944), Dương Đình Nghệ's son-in-law, defeated the Southern Han fleet at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (938). He then proclaimed himself King Ngô, established a monarchy government in Cổ Loa and effectively began the age of independence for Vietnam.

Dynastic Period (939 – 1945)

The basic nature of Vietnamese society changed little during the nearly 1,000 years between independence from China in the 10th century and the French conquest in the 19th century. Viet Nam, named Đại Việt (Great Viet) was a stable nation, but village autonomy was a key feature. Villages had a unified culture centered around harmony related to the religion of the spirits of nature and the peaceful nature of Buddhism. While the sovereign was the ultimate source of political authority, a saying was, "The Sovereign's Laws end at the village gate". The sovereign was the final dispenser of justice, law, and supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces, as well as overseer of religious rituals. Administration was carried out by mandarins who were trained exactly like their Chinese counterparts (i.e. by rigorous study of Confucian texts). Overall, Vietnam remained very efficiently and stably governed except in times of war and dynastic breakdown. Its administrative system was probably far more advanced than that of any other Southeast Asian states and was more highly centralized and stably governed among Asian states. No serious challenge to the sovereign's authority ever arose, as titles of nobility were bestowed purely as honors and were not hereditary. Periodic land reforms broke up large estates and ensured that powerful landowners could not emerge. No religious/priestly class ever arose outside of the mandarins either. This stagnant absolutism ensured a stable, well-ordered society, but also resistance to social, cultural, or technological innovations. Reformers looked only to the past for inspiration.

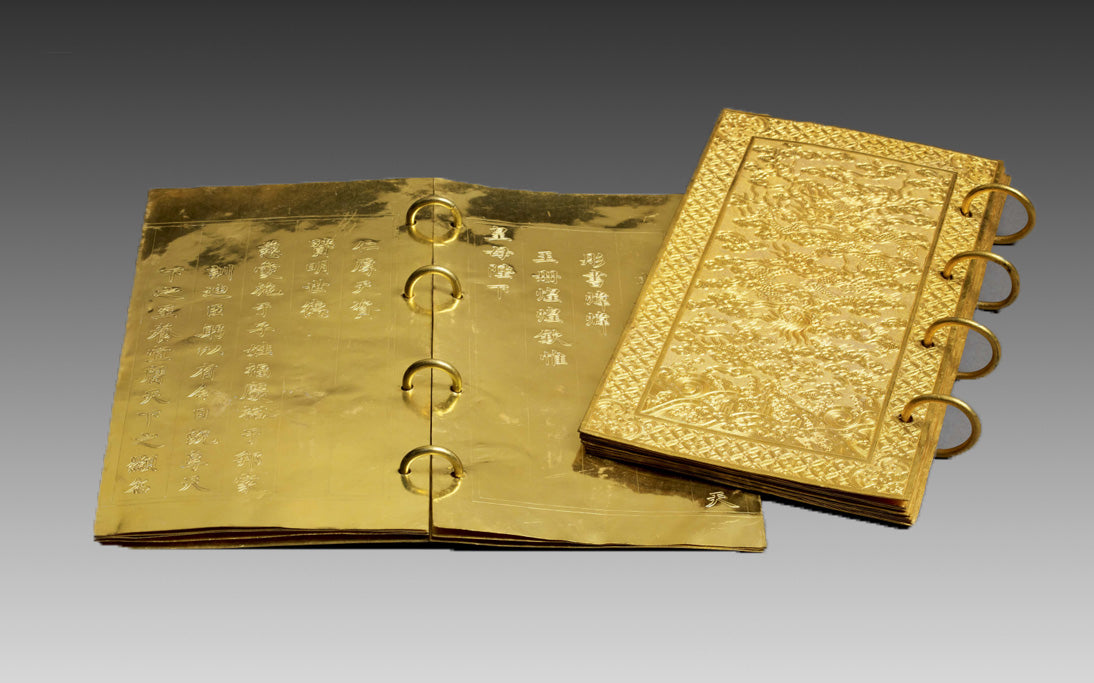

Literacy remained the province of the upper classes. Originally, only Chinese character was used to write, but by the 11th century, a set of derivative characters known as Chữ Nôm (a logographic writing system formerly used to write the Vietnamese language) emerged that allowed native Vietnamese words to be written. However, it remained limited to poetry, literature, and practical texts like medicine while all state and official documents were written in Classical Chinese. Aside from some mining and fishing, agriculture was the primary activity of most Vietnamese, and economic development and trade were not promoted or encouraged by the state.

Ngô, Đinh, and Anterior Lê dynasties (939 – 1009)

Ngô Quyền in 939 declared himself king, but died after only 6 years. His untimely death after a short reign resulted in a power struggle for the throne, resulting in the country's first major civil war, the upheaval of the Twelve Warlords (Loạn Thập Nhị Sứ Quân). The war lasted from 944 to 968, until the clan led by Đinh Bộ Lĩnh defeated the other warlords, unifying the country. Đinh Bộ Lĩnh founded the Đinh Dynasty in 968 and proclaimed himself Đinh Tiên Hoàng (Đinh the Majestic Emperor) and renamed the country from Tĩnh Hải Quân to Đại Cồ Việt (literally "Great Viet"), with its capital in the city of Hoa Lư (Ninh Bình Province). In relations with China since Đinh Bộ Lĩnh, Vietnamese dynasties had considered their leaders "kings" although they had still implicitly considered their leaders emperors.

In 979, Emperor Đinh Tiên Hoàng and his crown prince Đinh Liễn were assassinated by Đỗ Thích, a government official, leaving his lone surviving son, the 6-year-old Đinh Toàn, to assume the throne. Taking advantage of the situation, the Song dynasty invaded Đại Cồ Việt. Facing such a grave threat to national independence, the commander of the armed forces, (Thập Đạo Tướng Quân) Lê Hoàn took the throne, replaced the house of Đinh and established the Anterior Lê Dynasty. A capable military tactician, Lê Hoan realized the risks of engaging the mighty Song troops head on; thus, he tricked the invading army into Chi Lăng Pass, then ambushed and killed their commander, quickly ending the threat to his young nation in 981. The Song dynasty withdrew their troops and Lê Hoàn was referred to in his realm as Emperor Đại Hành (Đại Hành Hoàng Đế). Emperor Lê Đại Hành was also the first Vietnamese monarch who began the southward expansion process against the kingdom of Champa.

Emperor Lê Đại Hành's death in 1005 resulted in infighting for the throne amongst his sons. The eventual winner, Lê Long Đĩnh, became the most notorious tyrant in Vietnamese history. He devised sadistic punishments of prisoners for his own entertainment and indulged in deviant sexual activities. Toward the end of his short life – he died at the age of 24 – Lê Long Đĩnh had become so ill, that he had to lie down when meeting with his officials in court.

Lý Dynasty, Trần Dynasty and Hồ Dynasty (1009 – 1407)

When the emperor Lê Long Đĩnh died in 1009, a palace guard commander named Lý Công Uẩn was nominated by the court to take over the throne, and founded the Lý dynasty.This event is regarded as the beginning of another golden era in Vietnamese history, with the following dynasties inheriting the Lý dynasty's prosperity and doing much to maintain and expand it. The way Lý Công Uẩn ascended to the throne was rather uncommon in Vietnamese history. As a high-ranking military commander residing in the capital, he had all opportunities to seize power during the tumultuous years after Emperor Lê Hoàn's death, yet preferring not to do so out of his sense of duty. He was in a way being "elected" by the court after some debate before a consensus was reached.

The Lý monarchs are credited for laying down a concrete foundation for the nation of Vietnam. In 1010, Lý Công Uẩn issued the Edict on the Transfer of the Capital, moving the capital Đại Cồ Việt from Hoa Lư, a natural fortification surrounded by mountains and rivers, to the new capital, Đại La (Hanoi), which was later renamed Thăng Long (Ascending Dragon) by Lý Công Uẩn, after allegedly seeing a dragon flying upwards when he arrived at the capital. Moving the capital, Lý Công Uẩn thus departed from the militarily defensive mentality of his predecessors and envisioned a strong economy as the key to national survival. The third emperor of the dynasty, Lý Thánh Tông renamed the country "Đại Việt" (大越, Great Viet). Successive Lý emperors continued to accomplish far-reaching feats: building a dike system to protect rice farms; founding the Quốc Tử Giám the first noble university; and establishing court examination system to select capable commoners for government positions once every three years; organizing a new system of taxation; establishing humane treatment of prisoners. Women were holding important roles in Lý society as the court ladies were in charge of tax collection. Neighboring Dali kingdom's Vajrayana Buddhism traditions also had influences on Vietnamese beliefs at the time. Lý kings adopted both Buddhism and Taoism as state religions.

The Vietnamese during Lý dynasty had one major war with Song China, and a few invasive campaigns against neighboring Champa in the south. The most notable conflict took place on Chinese territory Guangxi in late 1075. Upon learning that a Song invasion was imminent, the Vietnamese army under the command of Lý Thường Kiệt, and Tông Đản used amphibious operations to preemptively destroy three Song military installations at Yongzhou, Qinzhou, and Lianzhou in Guangdong and Guangxi, and killed 100,000 Chinese. The Song dynasty took revenge and invaded Đại Việt in 1076, but the Song troops were held back at the Battle of Như Nguyệt River commonly known as the Cầu river (Bắc Ninh) about 40 km from the current capital, Hanoi. Neither side was able to force a victory, so the Vietnamese court proposed a truce, which the Song emperor accepted. Champa and the powerful Khmer Empire took advantage of Đại Việt's distraction with the Song to pillage Đại Việt's southern provinces. Together they invaded Đại Việt in 1128 and 1132. Further invasions followed in the subsequent decades.

Toward the declining Ly monarch's power in the late 12th century, the Trần clan from Nam Định eventually rise to power. In 1224, powerful court minister Trần Thủ Độ forced the emperor Lý Huệ Tông to become a Buddhist monk and Lý Chiêu Hoàng, Huệ Tông's 8-year-old young daughter, to become ruler of the country. Trần Thủ Độ then arranged the marriage of Chiêu Hoàng to his nephew Trần Cảnh and eventually had the throne transferred to Trần Cảnh, thus begun the Trần dynasty.

Trần Thủ Độ viciously purged members of the Lý nobility; some Lý princes escaped to Korea, including Lý Long Tường. After the purge, the Trần emperors ruled the country in similar manner to the Lý kings. Noted Trần monarch accomplishments include the creation of a system of population records based at the village level, the compilation of a formal 30-volume history of Đại Việt (Đại Việt Sử Ký) by Lê Văn Hưu, and the rising in status of the Nôm script, a system of writing for Vietnamese language. The Trần dynasty also adopted a unique way to train new emperors: when a crown prince reached the age of 18, his predecessor would abdicate and turn the throne over to him, yet holding the title of Retired Emperor (Thái Thượng Hoàng), acting as a mentor to the new Emperor.

During the Trần dynasty, the armies of the Mongol Empire and the Mongol Yuan dynasty of China under Mongke Khan and Kublai Khan Invaded Đại Việt in 1258, 1285 and 1287-88. Đại Việt repelled all attacks of the Yuan Mongols during the reign of Kublai Khan. Three Mongol armies said to have numbered from 300,000 to 500,000 men were defeated. The key to Annam's successes was to avoid the Mongols' strength in open field battles and city sieges—the Trần court abandoned the capital and the cities. The Mongols were then countered decisively at their weak points, which were battles in swampy areas such as Chương Dương, Hàm Tử, Vạn Kiếp and on rivers such as Vân Đồn and Bạch Đằng. The Mongols also suffered from tropical diseases and loss of supplies to Trần army's raids. The Yuan-Trần war reached its climax when the retreating Yuan fleet was decimated at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288). The military architect behind Annam's victories was Commander Trần Quốc Tuấn, more popularly known as Trần Hưng Đạo. To avoid further disastrous campaigns, the Tran and Champa acknowledged Mongol supremacy.

In 1288, Venetian eẽplorer Marco Polo visited Champa and Đại Việt. It was also during this period that the Vietnamese waged war against the southern kingdom of Champa, continuing the Vietnamese long history of southern expansion that had begun shortly after gaining independence in the 10th century. Often, they encountered strong resistance from the Chams. After the successful alliance with Champa during the Mongol invasion, king Trần Nhân Tông of Đại Việt gained two Champa provinces, located around present-day Huế, through the peaceful means of the political marriage of Princess Huyền Trân to Cham king Jaya Simhavarman III. Not long after the nuptials, the king died, and the princess returned to her northern home to avoid a Cham custom that would have required her to join her husband in death. Champa was made a tributary state of Vietnam in 1312, but ten years later they regained independence and eventually waged a 30-years long war against the Vietnamese, to regain these lands and encouraged by the decline of Đại Việt in the course of the 14th century. Cham troops led by king Chế Bồng Nga (Cham: Po Binasuor or Che Bonguar, r. 1360–1390) killed king Trần Duệ Tông through a battle in Viijaya (1377). Multiple Cham northward invasions from 1371 to 1390 put Vietnamese capital Thăng Long and Vietnamese economy in destruction. However, in 1390 the Cham naval offensive against Hanoi was halted by the Vietnamese general Trần Khát Chân, whose soldiers made use of cannons.

The wars with Champa and the Mongols left Đại Việt exhausted and bankrupt. The Trần family was in turn overthrown by one of its own court officials, Hồ Quý Ly. Hồ Quý Ly forced the last Trần emperor to abdicate and assumed the throne in 1400. He changed the country name to Đại Ngu and moved the capital to Tây Đô, Western Capital (Thanh Hóa). Thăng Long was renamed Đông Đô, Eastern Capital. Although widely blamed for causing national disunity and losing the country later to the Minh Empire, Hồ Quý Ly's reign actually introduced a lot of progressive, ambitious reforms, including the addition of mathematics to the national examinations, the open critique of Confucian philosophy, the use of paper currency in place of coins, investment in building large warships and cannons, and land reform. He ceded the throne to his son, Hồ Hán Thương, in 1401 and assumed the title Thái Thượng Hoàng, in similar manner to the Trần kings.

Fourth Era of Northern Domination (1407 – 1427)

In 1407, under the pretext of helping to restore the Trần monarchs, Chinese Ming troops invaded Đại Ngu and captured Hồ Quý Ly and Hồ Hán Thương. The Hồ family came to an end after only 7 years in power. The Ming occupying force annexed Đại Ngu into the Ming Empire after claiming that there was no heir to the Trần throne. Vietnam, weakened by dynastic feuds and the wars with Champa, quickly succumbed. The Ming conquest was harsh. Vietnam was annexed directly as a province of China, the old policy of cultural assimilation again imposed forcibly, and the country was ruthlessly exploited. However, by this time, Vietnamese nationalism had reached a point where attempts to sinicize them could only strengthen further resistance. Almost immediately, loyalists started a resistance war Trần. The resistance, under the leadership of Trần Quý Khoáng at first gained some advances, yet as Trần Quý Khoáng executed two top commanders out of suspicion, a rift widened within his ranks and resulted in his defeat in 1413.

Restored Dai Viet Period (1428 – 1527). Later Lê Dynasty – Initial Period (1428 – 1527)

In 1418, Lê Lợi was the son of a wealthy aristocrat in Thanh Hóa, led the Lam Sơn uprising against the Ming from his base of Lam Sơn (Thanh Hóa). Overcoming many early setbacks and with strategic advice from Nguyễn Trãi, Lê Lợi's movement finally gathered momentum. In September 1426, the Lam Sơn rebellion marched northward, ultimately defeated the Ming army in the Battle of Tốt Động – Chúc Động in south of Hanoi by using cannons. Then Lê Lợi's forces launched a siege at Đông Quan (Hanoi), the capital of the Ming occupation. The Xuande Emperor of Ming China responded by sent two reinforcement forces of 122,000 men, but Lê Lợi staged an ambush and killed the Ming commander Liu Shan in Chi Lăng. Ming troops at Đông Quan surrendered. The Lam Sơn rebels defeated 200,000 Ming soldiers.

In April 1428, Lê Lợi reestablished the independence of Vietnam under his Lê dynasty. Lê Lợi renamed the country back to Đại Việt and moved the capital back to Thăng Long, renamed it Đông Kinh.

The territory of Đại Việt during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông (1460–1497), including conquests in Muang Phuan and Champa.

The Lê emperors carried out land reforms to revitalize the economy after the war. Unlike the Lý and Trần emperors, who were more influenced by Buddhism, the Lê emperors leaned toward Confucianism. A comprehensive set of laws, the Hồng Đức code was introduced in 1483 with some strong Confucian elements, yet also included some progressive rules, such as the rights of women. Art and architecture during the Lê dynasty also became more influenced by Chinese styles than during previous Lý and Trần dynasties. The Lê dynasty commissioned the drawing of national maps and had Ngô Sĩ Liên continue the task of writing Đại Việt's history up to the time of Lê Lợi.

Overpopulation and land shortages stimulated a Vietnamese expansion south. In 1471, Đại Việt troops led by emperor Lê Thánh Tông invaded Champa and captured its capital Vijaya. This event effectively ended Champa as a powerful kingdom, although some smaller surviving Cham states lasted for a few centuries more. It initiated the dispersal of the Cham people across Southeast Asia. With the kingdom of Champa mostly destroyed and the Cham people exiled or suppressed, Vietnamese colonization of what is now central Vietnam proceeded without substantial resistance. However, despite becoming greatly outnumbered by Vietnamese settlers and the integration of formerly Cham territory into the Vietnamese nation, the majority of Cham people nevertheless remained in Vietnam and they are now considered one of the key minorities in modern Vietnam. Vietnamese armies also raided the Mekong Delta, which the decaying Khmer Empire could no longer defend. The city of Huế, founded in 1600 lies close to where the Champa capital of Indrapura once stood. In 1479, Lê Thánh Tông also campaigned against Laos in the Vietnam-Laos War and captured its capital Luang Prabang, in which later the city was totally ransacked and destroyed by the Vietnamese. He made further incursions westwards into the Irrawaddy River region in modern-day Burma before withdrawing. After the death of Lê Thánh Tông, Đại Việt fell into a swift decline (1497–1527), with 6 rulers in within 30 years of failing economy, natural disasters and rebellions raged through the country. European traders and missionaries, reaching Vietnam in the midst of the Age of Discovery, were at first Portuguese and started spreading Christianity since 1533

Decentralized Period (1527 – 1802). Mạc and Later Lê Dynasties – Restoration Period (1527 – 1789)

The Lê dynasty was overthrown by its general named Mạc Đăng Dung in 1527. He killed the Lê emperor and proclaimed himself emperor, starting the Mạc dynasty. After defeating many revolutions for two years, Mạc Đăng Dung adopted the Trần dynasty's practice and ceded the throne to his son, Mạc Đăng Doanh, and he became Thái Thượng Hoàng (Emperor Emeritus or Grand Emperor).

Meanwhile, Nguyễn Kim, a former official in the Lê court, revolted against the Mạc and helped king Lê Trang Tông restore the Lê court in the Thanh Hóa area. Thus a civil war began between the Northern Court (Mạc) and the Southern Court (Restored Lê). Nguyễn Kim's side controlled the southern part of Annam (from Thanhhoa to the south), leaving the north (including Đông Kinh-Hanoi) under Mạc control. When Nguyễn Kim was assassinated in 1545, military power fell into the hands of his son-in-law, Trịnh Kiểm. In 1558, Nguyễn Kim's son, Nguyễn Hoàng, suspecting that Trịnh Kiểm might kill him as he had done to his brother to secure power, asked to be governor of the far south provinces around present-day Quảng Bình to Bình Định. Hoàng pretended to be insane, so Kiểm was fooled into thinking that sending Hoàng south was a good move as Hoàng would be quickly killed in the lawless border regions. However, Hoàng governed the south effectively while Trịnh Kiểm, and then his son Trịnh Tùng, carried on the war against the Mạc. Nguyễn Hoàng sent money and soldiers north to help the war but gradually he became more and more independent, transforming their realm's economic fortunes by turning it into an international trading post.

The civil war between the Lê-Trịnh and Mạc dynasties ended in 1592, when the army of Trịnh Tùng conquered Thăng Long (nowadays Hanoi) and executed king Mạc Mậu Hợp. Survivors of the Mạc royal family fled to the northern mountains in the province of Cao Bằng and continued to rule there until 1677 when Trịnh Tạc conquered this last Mạc territory. The Lê monarchs, ever since Nguyễn Kim's restoration, only acted as figureheads. After the fall of the Mạc dynasty, all real power in the north belonged to the Trịnh lords. Meanwhile, the Ming court reluctantly decided on a military intervention into the Vietnamese civil war, but Mạc Đăng Dung offered ritual submission to the Ming Empire, which was accepted. Since the late 16th century, trades and contacts between Japan and Vietnam increased as they established relationship in 1591. The Tokuhawa Shogunate of Japan and governor Nguyễn Hoàng of Quảng Nam exchanged total 34 letters from 1589 to 1612, and a Japanese town was established in the city of Hội An in 1604.

Trịnh and Nguyễn Lords (1600 – 1777)

In the year 1600, Nguyễn Hoàng also declared himself Lord (officially "Vương", popularly "Chúa") and refused to send more money or soldiers to help the Trịnh. He also moved his capital to Phú Xuân, modern-day Huế. Nguyễn Hoàng died in 1613 after having ruled the south for 55 years. He was succeeded by his 6th son, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, who likewise refused to acknowledge the power of the Trịnh, yet still pledged allegiance to the Lê monarch.

Trịnh Tráng succeeded Trịnh Tùng, his father, upon his death in 1623. Tráng ordered Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên to submit to his authority. The order was refused twice. In 1627, Trịnh Tráng sent 150,000 troops southward in an unsuccessful military campaign. The Trịnh were much stronger, with a larger population, economy and army, but they were unable to vanquish the Nguyễn, who had built two defensive stone walls and invested in Portuguese artillery.

The Trịnh-Nguyễn war lasted from 1627 until 1672. The Trịnh army staged at least seven offensives, all of which failed to capture Phú Xuân. For a time, starting in 1651, the Nguyễn themselves went on the offensive and attacked parts of Trịnh territory. However, the Trịnh, under a new leader, Trịnh Tạc, forced the Nguyễn back by 1655. After one last offensive in 1672, Trịnh Tạc agreed to a truce with the Nguyễn Lord Nguyễn Phúc Tần.

As such, between 1600 and 1775, the two powerful families partitioned the country: the Nguyễn lords ruled Đàng Trong (the South), while the Trịnh lords controlled the Đàng Ngoài (the North).

Tây Sơn Dynasty (1778 – 1802)

In 1771, the Tây Sơn revolution broke out in Quy Nhon, which was under the control of the Nguyễn lord. The leaders of this revolution were three brothers named Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ, and Nguyễn Huệ, not related to the Nguyễn lord's family. In 1773, Tây Sơn rebels took Quy Nhon as the capital of the revolution. Tây Sơn brothers' forces attracted many poor peasants, workers, Christians, ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands and Cham people who had been oppressed by the Nguyễn Lord for a long time, and also attracted to ethnic Chinese merchant class, who hope the Tây Sơn revolt will spare down the heavy tax policy of the Nguyễn Lord, however their contributions later were limited due to Tây Sơn's nationalist anti-Chinese sentiment. By 1776, the Tây Sơn had occupied all of the Nguyễn Lord's land and killed almost the entire royal family. The surviving prince Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (often called Nguyễn Ánh) fled to Siam, and obtained military support from the Siamese king. Nguyễn Ánh came back with 50,000 Siamese troops to regain power, but was defeated at the Battle of Rạch Gầm-Xoài Mút and almost killed. Nguyễn Ánh fled Vietnam, but he did not give up.

The Tây Sơn army commanded by Nguyễn Huệ marched north in 1786 to fight the Trịnh Lord, Trịnh Khải. The Trịnh army failed and Trịnh Khải committed suicide. The Tây Sơn army captured the capital in less than two months. The last Lê emperor, Lê Chiêu Thống, fled to Qing China and petitioned the Qianlong Emperor in 1788 for help. The Qianlong Emperor supplied Lê Chiêu Thống with a massive army of around 200,000 troops to regain his throne from the usurper. In December 1788, Nguyễn Huệ–the third Tây Sơn brother–proclaimed himself Emperor Quang Trung and defeated the Qing troops with 100,000 men in a surprise 7-day campaign during the lunar new year festival. There was even a rumor saying that Quang Trung had also planned to conquer China, although it was unclear. During his reign, Quang Trung envisioned many reforms but died by unknown reason on the way march south in 1792, at the age of 40. During the reign of Emperor Quang Trung, Đại Việt was in fact divided into three political entities. The Tây Sơn leader, Nguyễn Nhạc, ruled the centre of the country from his capital Quy Nhon. Emperor Quang Trung ruled the north from the capital Phú Xuân Huế. In the South, he officially funded and trained the Pirates of the South China Coast – one of the most strongest and feared pirate army in the world late 18th century – early 19th century. Nguyễn Ánh, assisted by many talented recruits from the South, captured Gia Định (Saigon) in 1788 and established a strong base for his force.

In 1784, during the conflict between Nguyễn Ánh, the surviving heir of the Nguyễn lords, and the Tây Sơn dynasty, a French Roman Catholic prelate, Pigneaux de Behaine, sailed to France to seek military backing for Nguyễn Ánh. At Louis XVI's court, Pigneaux brokered the Little Treaty of Versailles which promised French military aid in exchange for Vietnamese concessions. However, because of the French Revolution, Pigneaux's plan failed to materialize. He went to the French territory of Puducherry (India), and secured two ships, a regiment of Indian troops, and a handful of volunteers and returned to Vietnam in 1788. One of Pigneaux's volunteers, Jean-Marie Dayot, reorganized Nguyễn Ánh's navy along European lines and defeated the Tây Sơn at Quy Nhon in 1792. A few years later, Nguyễn Ánh's forces captured Gia Định (nowadays Ho Chi Minh city or Saigon as another name), where Pigneaux died in 1799. Another volunteer, Victor Olivier de Puymanel would later build the Gia Định fort in central Saigon.

After Quang Trung's death in September 1792, the Tây Sơn court became unstable as the remaining brothers fought against each other and against the people who were loyal to Nguyễn Huệ's young son. Quang Trung's 10-years-old son Nguyễn Quang Toản succeeded the throne, became Emperor Cảnh Thịnh, the third ruler of the Tây Sơn dynasty. In the South, lord Nguyễn Ánh and the Nguyễn royalists were assisted with French, Chinese, Siamese and Christian supports, sailed north in 1799, capturing Tây Sơn's stronghold Quy Nhon. In 1801, his force took Phú Xuân, the Tây Sơn capital. Nguyễn Ánh finally won the war in 1802, when he sieged Thăng Long (Hanoi) and executed Nguyễn Quang Toản, along with many Tây Sơn royals, generals and officials. Nguyễn Ánh ascended the throne and called himself Emperor Gia Long. Gia is for Gia Định, the old name of Saigon; Long is for Thăng Long, the old name of Hanoi. Hence Gia Long implied the unification of the country. The Nguyễn dynasty lasted until Bảo Đại's abdication in 1945. As China for centuries had referred to Đại Việt as Annam, Gia Long asked the Manchu Qing emperor to rename the country, from Annam to Nam Việt. To prevent any confusion of Gia Long's kingdom with Zhao Tuo's ancient kingdom (Nanyue), the Manchu emperor reversed the order of the two words to Việt Nam. The name Vietnam is thus known to be used since Emperor Gia Long's reign. Recently historians have found that this name had existed in older books in which Vietnamese referred to their country as Vietnam.

The Period of Division with its many tragedies and dramatic historical developments inspired many poets and gave rise to some Vietnamese masterpieces in verse, including the epic poem The Tale of Kieu (Truyện Kiều) by Nguyễn Du, Song of a Soldier's Wife (Chinh Phụ Ngâm) by Đặng Trần Côn and Đoàn Thị Điểm, and a collection of satirical, erotically charged poems by a female poet, Hồ Xuân Hương.